Hypertension at Porsche

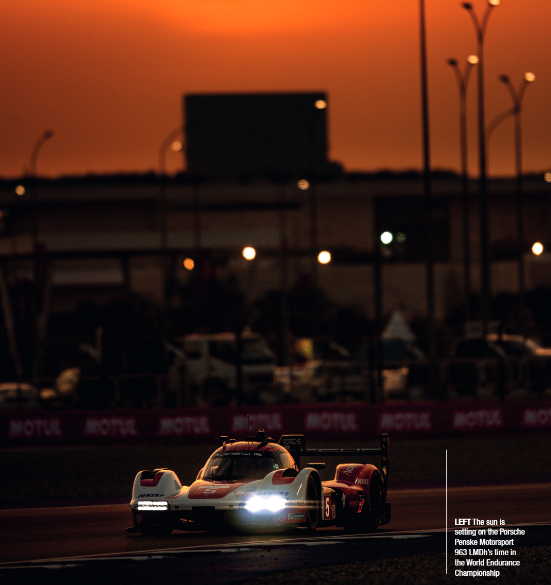

PORSCHE has axed its factory entries with Penske Racing in next year’s World Endurance Championship. It’s not the first withdrawal of a major manufacturer from the series in the Hypercar era; Lamborghini took that undistinguished honour. But it is the most significant.

That means this has to be regarded as the first bump in the road since the start of the new golden era of sportscar racing in 2023 even as more manufacturers are gearing up to join the party.

The reasons are twofold. The first is that the withdrawal concerns two of the most distinguished names in worldwide motorsport. Porsche is arguably the sportscar manufacturer, a marque that has been ever present in long-distance racing for more than 70 years. It is also the most successful manufacturer in the history of the Le Mans 24 Hours with 19 victories.

Penske, meanwhile, has won just about everything worth winning in motorsport including US open-wheelers, NASCAR and sportscar racing., not forgetting lone F1 grand prix victory back in 1976. Unlike Lamborghini, Porsche is also a WEC frontrunner: it won the 2024 drivers’ title and it had an outside chance of retaining its crown heading into the 2025 season finale in Bahrain on November 8.

The second reason the decision not to race on with the Porsche Penske Motorsport 963 LMDhs in 2026 can be described as a ‘bump’ is – at least partly – the rationale behind it. Porsche Motorsport had to make savings, or at least to be seen to be making savings, at a time when the marque is in trouble. Road car sales are down and back in the summer its CEO Oliver Blume announced a plan to reduce the workforce by 10% before 2029 as he outlined a future in which Porsche sales peak at 250,000 a year rather than the 300,000-plus of 2024.

As engrained in Porsche’s psyche as motorsport is, it still has to be regarded as something of a frivolity when rank and file members of the workforce are facing redundancy. Porsche had to lose one of its three factory programmes, and it was WEC that got the chop. This choice has to be a worry for the WEC and its organiser, the FIA and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest.

Porsche’s participation in the FIA Formula E World Championship dating back to the 2019/2020 season was safe from the get-go.

The German manufacturer has made much of its three-pronged approach to motorsport that takes its lead from its road car range: it involves full electric vehicles, hybrids and pure combustion cars. There isn’t anywhere else for it to race a full-electric car save for Formula E which, pertinently, is heading into a new era with the introduction of the Gen4 car for the Season 13 campaign starting at the end of 2026.

That made it a straight choice between the WEC Hypercar and IMSA SportsCar Championship GTP class assaults with the 963 LMDh developed out of the Multimatic Motorsports chassis spine. Thomas Laudenbach, vice-president of Porsche Motorsport, has refused to go into the intricacies of the decision-making process, but he has conceded there were both sporting and marketing considerations.

“Motorsport belongs to the company and motorsport has to give a contribution: the financial aspect,” says Laudenbach. The financial aspect refers to the fact that Porsche sells more cars in North America than anywhere else.

It is also where it has enjoyed the most success with the 963 since the car cameon 2023.

It won the drivers’, manufacturers’ and teams’ crowns in year two and retained them at this year’s Petit Le Mans IMSA finale at Road Atlanta in October, also claiming a clean sweep of the IMSA Michelin Endurance Cup silverware. Back- to-back victories at the Daytona 24 Hours and the Sebring 12 Hours at the start of the campaign helped push it to those titles.

Asked if the successes in North America and the fact that there appears to be a more level playing field in IMSA than in WEC was a factor, Laudenbach suggests that this author had “answered your own question”. He added: “The original idea was you can build one car, you can race in both championships and we can control costs to a feasible budget, and race, of course, on a level playing field. It didn’t work out everywhere the same. This, of course, had an influence on our decision.”

There is one key difference between the IMSA and WEC campaigns: PPM has won Daytona twice with the 963, this year and last, meaning that Porsche’s tally in the US enduro has now surpassed the 19 Le Mans wins. The circumstances of its second- place finish at the WEC blue riband this year appear to grate.

Laudenbach doesn’t mention the Balance of Performance when talking about Le Mans for a simple reason: he’s not allowed to under the WEC sporting regulations. But he is clearly saying that it didn’t do its job.

“Second place is not bad if you look at the competition out there, but on the other side it did hurt because the #6 car was close to what I would call a perfect race,” he says. “Frankly speaking the #6 should have won the race, full stop.” The #6 entry shared by Kevin Estre, Laurens Vanthoor and Matt Campbell was delayed only by a slow puncture early in the race, whereas the winning Ferrari 499P Le Mans Hypercar entry and the third-placed factory car from the Italian manufacturer suffered multiple hiccups. If you accept that the BoP is meant to level the playing field to such an extent that who wins and who doesn’t should come down to driver performance, strategy and reliability then the BoP missed the mark at Le Mans. On the first and last of those criteria Porsche was definitely ahead of Ferrari over the course of the 24 Hours.

Ahead of the decision to leave the WEC as a factory Laudenbach suggested there were “things we can improve” in the WEC. “We are having a very good dialogue, but the only thing I would say at this stage is that for sure we need improvement,” he said at the Austin round in September. He again made a veiled reference to the BoP when he added: “We have seen a lot of results that are questionable.”

Is there a trend?

No is the definitive answer to that one: there is no link between the Porsche and Lamborghini decisions to quit WEC. A unique set of circumstances is always behind the decision when a manufacturer withdraws from any high- level series. The explanation of the Italian manufacturer’s departure from WEC is quite different to Porsche’s.

Lamborghini pulled out of the WEC ahead of the 2025 season, instead focusing on a one-car IMSA campaign in the five IMSA enduros. That programme, conducted under its own banner with Riley Motorsports as a service provider, was axed in the late summer. Officially the SC63 is on hold, but few expect to see the car race again. There’s an irony to that given that it notched up its best result — and most competitive performance — on what can be presumed its final hurrah at Road Atlanta.

A machine that was racing for the second time with a revised rear suspension design introduced at the previous IMEC round at Indianapolis finished fourth and it was right up there among the quickest cars over the final four hours of the race uninterrupted by yellow flags.

Lamborghini scaled back its LMDh programme in year two when it was forced to go it alone after the split with its original partners, Iron Lynx and its DC Racing Solutions parent company. In year one it entered one car in the full WEC and one in four of the five IMSA enduros, but new rules in the world championship forced Hypercar manufacturers to enter two cars from this year. Lamborghini blamed the new regulation for its decision in its statement announcing the WEC withdrawal.

That should be regarded as a simplification of the situation. It would be better described as the start of the breakdown of the relationship with Iron Lynx. As rumours of the Lambo pull-out were gathering, the Italian team was saying it was ready to run two cars in 2025. What it wasn’t ready to do, it seems, was pay for them.

Iron Lynx, whose WEC set-up incorporated the Prema Racing single-seater team that came into the DC Solutions empire in September 2021, was key to getting the Lamborghini LMDh programme off the ground. Or rather the finance it brought to the programme was. But what it apparently wasn’t prepared to do was step up its funding to run a car that was proving uncompetitive in both arenas. Lamborghini, part of the Volkswagen group but a relatively small company in contrast to many of its rivals in WEC and IMSA, didn’t have the resources to fill the financial gap.

A year on, Lambo has probably raced for the last time with its LMDh because the marque has failed to find a partner to make the contribution it needs to continue in IMSA. The uncompetitiveness of the SC63 always made that unlikely. Its decision to pause the programme was made before the rear suspension upgrade under evo joker rules that have crossed over into LMDh from LMH.

There is nothing to suggest that Atlanta was anything but the final race for the SC63. It appears there are no plans to put the car back in the Windshear wind tunnel in North Carolina for the new round of homologation testing. All cars competing in IMSA and the WEC will now go into the tunnel, whereas previously only LMDhs – including the Alpine that only competes in WEC and the Aston Martin LMH – had gone to the States for this section of the homologation process.

WEC-only LMH cars were put through their paces in the Sauber tunnel, which is now no longer available after Audi’s takeover of the Swiss F1 team.

What happens next for Porsche?

The German manufacturer will race on in IMSA with two PPM 963s. It will again be represented in GTP by the privateer JDC-Miller MotorSports squad: the Minnesota- based team was on the full-season entry list revealed at Petit.

Porsche pledged to make its LMDh available to privateers from the get-go. After all, it was named in tribute to the 962, a car that raced in the hands of the official Holbert Racing team and customers from its maiden year in IMSA in 1984. Laudenbach insists there will be no change.

“The only thing I can say is that the decision not to participate in 2026 with our factory programme has absolutely no effect on our customer programme,” he says. “Don’t forget that customer racing up from club sport to high-level professional racing is very important for Porsche, and this remains.”

Proton Competition ran a 963 in the full WEC this year after blooding its first chassis in the series post-Le Mans in 2023, joining the British Jota squad. Jota ran a solo car from Spa onwards then expanded to two cars last season before landing a deal to become Cadillac’s factory representative in 2025. Proton has two chassis: it has run a car in IMSA too, an entry for the enduros this year ending two races early after a shunt at Watkins Glen in June.

The German team has been on the reserve list of Le Mans for the past two years with its second car and it has aspirations to expand for 2026: it is known to be working on a deal to partner with another operation to facilitate that.

What is unclear is whether Porsche needs to have two customer cars on the grid if it is to maintain a presence in the WEC with the 963. The rules as they stand suggest that they do, though they were clearly written for a scenario where the OEM is racing with a factory team and competing for manufacturers’ world championship points with any privateers scoring in the FIA World Cup for Hypercar Teams’ classifications. There is also a fee for a manufacturer that comes with competing in Hypercar that is over €500,000.

When asked about this, Laudenbach dodges the question, reiterating his point that the WEC decision does not impact its customer programme. Yet he did hint that the question really needs to be put to the series organisers. “You are asking the wrong person,” he says. “If a customer wants to race, that’s not up to us.” But he added: “Why shouldn’t we continue the way it is?” Laudenbach stresses that the decision to leave the WEC is a fresh one and how its wider impact shakes out remains unknown for the moment. That includes whether PPM could be at Le Mans next year. It has in theory won an automatic entry for the centrepiece WEC round in June. One of the three entries IMSA is allowed to award at its discretion has traditionally gone to the winner of the GTP teams’ title. “It is not a topic for right now,” says Laudenbach of the Le Mans entry. “This is something we will have to look at later on. There are too many question marks.”

One of those has to be whether Porsche and Penske would want to go to Le Mans with a single car. For the past three years it has gone with three: it got the IMSA entry last year and exploited the rules that allow Hypercar manufacturers to run an extra car or cars in 2023.

Another possibility is that Porsche could help Proton expand its entry and bolster its assault, perhaps with the loan of factory drivers and engineering support. It would not be without precedent. Back in 2016, Porsche and its Manthey factory team took a year out from the GTE Pro class while it was developing the mid-engined 911 RSR.

Proton fielded a solo 911 GT3-R with a line- up of works drivers in its place.

Could Porsche soon be back in WEC? Laudenbach, again, insists it’s too early to talk about that. He does, however, stress that Porsche remains committed to endurance racing. “What we have done is made an adjustment on our factory programmes,” he says. “That does not mean we have completely changed our philosophy and strategy.

“We cannot exclude that one day we will come back. If the day comes when we think it is feasible to come back, we will discuss it.” Porsche’s motorsport boss isn’t more specific than that. He chooses not to answer whether 2030 – when there is expected to be a realignment of the rules within the Hypercar division – would be an obvious time to return.

But Porsche has been one of the manufacturers leading the push towards more commonality between the LMDh and LMH rulesets. Laudenbach, again speaking at the Austin WEC round, stressed that it was both desirable and feasible. What appears to be on the table is a move towards the LMDh regulations, but one that allows more freedom for manufacturers. What seems to be being discussed is the possibility for an OEM being able to develop its own chassis rather than being forced to base its car on the spine provided by one of the four licensed constructors, ORECA Motorsport, Dallara Automobili, Multimatic Motorsports and Ligier Automotive. Or to make its own battery and Motor Generator Unit rather than using the off-the-shelf LMDh kit provided by Bosch Motorsport, Fortescue Zero (formerly Williams Advanced Engineering) and Xtrac. The former would be demanded by the likes of Ferrari, which insists a Ferrari can’t be built on the same chassis as a Cadillac or a Porsche; the latter by Toyota, which needs to be able to produce its own hybrid tech for what has always been a programme led on its benefits in terms of research and development rather than marketing value.

“This is absolutely possible,” said Laudenbach. “I think there is a solution for that. I fully accept a manufacturer saying ‘this is important to me’: everything I have heard so far can be solved. I am not saying it is easy, but I am pretty sure this is possible.”

On the chassis question, he added: “If I want to do my own within the rules of LMDh, where’s the problem? I don’t see a problem.” And on the hybrid conundrum: “If somebody says to me it is the most important thing that the hybrid system is my own, that’s fine. You just have to make a technical description of what is allowed.”

The drive to bring these regulations together appears to have wide support. Andreas Roos – head of motorsport at BMW, another marque in the LMDh camp – offers a similar opinion. “I don’t think it is a problem to have your own chassis or hybrid system,” he says. “We need to be clever and make the technical regulations in a certain way so no one has an advantage and the basic technical regulations are the same for everyone. For me this is possible.”

The first meeting to discuss the idea came during September at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris. The manufacturers are under instruction not to talk about what was decided or even discussed. But it can be said that a proposal to shift wholesale to the LMDh platform was thrown out along with any moves to try to introduce changes before 2030. A call from one manufacturer, almost certainly Ferrari, to do away with the BoP as early as next year was also shouted down.

Hypercar rules OK?

The 2030 date is significant. The FIA and ACO have made announcements about the future of Hypercar at Le Mans at each of the past two editions. In 2024, the homologation of the existing cars was extended by two years until the end of 2029. This year, the life of the class – as distinct from the cars – was prolonged by another three years through to 2032. That is where the push to somehow align the two rulebooks comes from.

Laudenbach suggested in Austin that the earlier the better for some kind of convergence. Other manufacturers appeared to agree. It is unlikely that the decision to stick with the status quo for another four years influenced Porsche’s decision to end its WEC participation and continue in IMSA. It seems that the axe was at least hovering over WEC, even if it had not fallen. Porsche didn’t shoot for outright glory at Le Mans between 1998 and victory number 16 with the 911 GT1-98 and the arrival of the 919 Hybrid in 2014. Yet after it bowed out of LMP1 in WEC after a hat-trick of wins at the French enduro in 2015-17, it was back after only five years away with its LMDh. So it’s anyone’s guess how long we will have to wait for victory number 20 for Porsche on the Circuit de la Sarthe.